The Capture of President Maduro — Trump’s Theatrical Triumph or a Democratic Trap?

The Week That Shaped the World — 2 - 9 January 2026

The Capture of Power — and Other Fault Lines Shaping the Week

The capture of President Maduro did more than shake Caracas — it exposed a broader fracture running through global politics. What Washington framed as decisive leadership looked, from the outside, like a carefully staged performance under domestic pressure. That tension between spectacle and consequence sets the tone for the entire week. From Kyiv’s search for a sustainable architecture of war and peace, to the Middle East’s shifting anchors and Iran’s rising volatility, power is being exercised loudly — and often impatiently. Markets, meanwhile, appear strangely detached, celebrating new records as geopolitical norms quietly erode. This digest traces those parallel movements: force replacing law, performance overtaking diplomacy, and stability increasingly treated as optional. The question is no longer where the next crisis will emerge, but how many will be absorbed before the system itself begins to bend.

“When power turns theatrical, the consequences rarely stay on stage.”

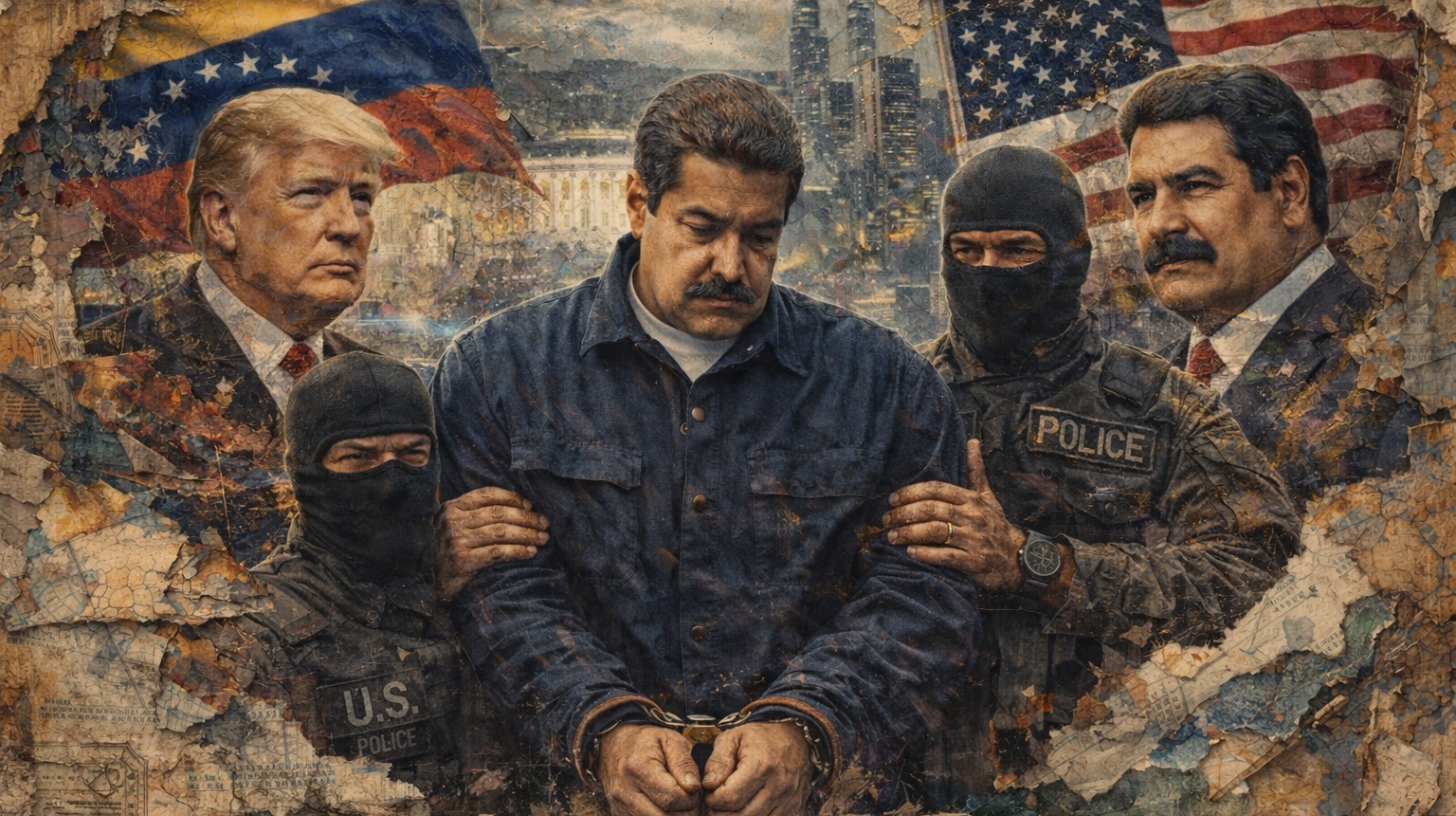

1. The Capture of President Maduro — Trump’s Theatrical Triumph or a Democratic Trap?

In our previous weekly digest, published just a day before events in Caracas unfolded, this editorial desk noted a sharp and unusual convergence of signals around Venezuela — diplomatic silence, intelligence leaks, and a sudden shift in Washington’s tone. At the time, we stopped short of predictions. In retrospect, the direction was unmistakable.

The capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro by U.S. special forces is, without question, one of the most dramatic geopolitical events of recent years. Washington presents the operation as a decisive blow against narco-terrorism and state criminality. The imagery — a head of state removed from his palace and placed before an American court — is designed to project strength, resolve and moral clarity.

Yet from a British vantage point, the episode raises more troubling questions than triumphant answers.

There is no legal ambiguity here: the seizure of a sitting president on foreign soil constitutes a gross violation of international law. Our editorial position is unambiguous — such actions, regardless of their target, erode the very framework that prevents the world from descending into rule by force. Precedents matter. And this one, once set, will be remembered by less restrained leaders with far fewer checks on their ambitions.

The political context in Washington cannot be ignored. Donald Trump is operating under intense domestic pressure. With midterm elections looming in November, failure to demonstrate tangible “wins” risks handing Congress to the Democrats — a scenario that would paralyse his presidency for the remaining two years. Against that backdrop, the temptation to perform the role of the decisive cowboy-in-chief becomes clear. Law, diplomacy and allied discomfort appear secondary.

Trump himself has not softened the message. Declaring himself the effective “emperor of the American hemisphere”, he has openly suggested that dozens of countries fall within the sphere of his personal will. Emboldened by the apparent success in Caracas, his rhetoric has expanded. Denmark has been warned that Greenland may be “bought or taken”. Canada, previously spoken of in similar tones, cannot miss the implication. Should such ambitions materialise, the United States would control North America outright — and South America by economic extension.

Our editorial assessment is that the Venezuelan operation itself may be far less heroic than advertised. Viewed through a sceptical British lens, it resembles not a bold extraction but a negotiated handover. Key figures within Venezuela’s elite appear to have traded loyalty for future influence. With Delcy Rodríguez already acting as the country’s de facto leader and oil deals quietly taking shape, the spectacle begins to look less like justice and more like choreography.

For theatrical effect, Washington has also hardened its tone towards Moscow. The seizure of two Russian tankers departing Venezuelan ports was widely portrayed as a humiliation of Vladimir Putin. In reality, it is difficult to see strategic substance behind the gesture. Russia loses little; retaliatory measures remain readily available. No one is preparing for a world war over two ageing vessels.

What remains is a pattern — force presented as order, spectacle sold as leadership. For the American voter, it may play well. For the rest of the world, it signals something more unsettling.

“When power stops respecting law, it does not create order — it merely teaches others to do the same.”

2. The Kyiv Accord — Peace, Deferred and Carefully Guarded

On 3 January, Kyiv briefly ceased to resemble a frontline capital and instead became a conference room for Europe’s future security architecture. National security advisers from the so-called “Coalition of the Willing” gathered to discuss what was framed as a post-war settlement — not an end to the conflict, but the shape of the peace that might follow it.

Among the topics quietly circulating around the table was the possibility of a multinational military presence in Ukraine after the war, with figures in the region of 30,000 troops mentioned in diplomatic discussions. Crucially, this was not a commitment, nor a finalised plan — rather a conceptual framework for what European officials describe as “security guarantees” once hostilities formally cease.

Alongside this sat broader ambitions: long-term recovery estimates that now approach $800 billion over the long term, and a shift toward embedding Ukraine permanently into a European-led defence posture. Support, it seems, is evolving into integration — but only on carefully negotiated terms, and only at a later stage.

From a British perspective, this is where the Kyiv Accord begins to feel less like reassurance and more like postponement. The question practically asks itself: why now, and why not earlier? If a coalition of willing states is prepared to deploy forces after the war, why is it unwilling to do so while Ukraine is still bleeding manpower at the front?

Ukrainian soldiers are expected to fight and die now, alone, while external forces discuss presence only once the shooting stops — when risks are lower, borders are clearer, and influence can be negotiated rather than earned. Peacekeeping, after all, is far less costly than war-fighting.

Our editorial reading is uncomfortable but difficult to ignore: many are prepared to divide responsibility after the war, but few are willing to share its cost while it is being fought. Ukraine is asked to hold the line today, so that others may help design the outcome tomorrow.

Peace, in Kyiv, increasingly resembles a project deferred — and carefully protected from those expected to pay for it first.

“Everyone wants a role in peace, but very few volunteer for the war that makes it possible.”

3. The Amman Summit — Europe Builds a Buffer, Not a Solution

On 8 January, Brussels briefly discovered geography. The EU–Jordan summit in Amman was presented as the birth of a more “proactive” Middle Eastern policy, though in truth it was something more modest — and more honest. For the first time, the European Union treated Jordan not as a recipient of aid packages and lectures, but as a functional partner in regional containment.

That distinction matters.

Amid the permanent instability of the Levant, Jordan’s greatest asset is not ambition, ideology, or influence. It is survivability. The kingdom has endured wars it did not start, refugees it did not invite, and crises it could not prevent. In European eyes, that resilience has now been repackaged as strategy. Amman is no longer merely stable; it is useful.

The summit framed Jordan as a “security bridge” — a phrase that sounds noble until one considers what it actually means. Energy corridors must be protected. Migration flows must be managed before they reach Europe’s borders. Chaos must be absorbed somewhere else. Jordan, by virtue of its geography and political discipline, fits the requirement.

An “integration agreement” was announced, widely described as unprecedented. In reality, it stops well short of integration in the European sense. There is no accession path, no shared sovereignty, no equal exposure to risk. What exists instead is functional alignment — cooperation without commitment, partnership without liability.

From a British perspective, this looks less like diplomacy aimed at resolving regional instability and more like architecture designed to keep it at a safe distance. Europe is not anchoring peace in the Middle East; it is anchoring itself against its consequences.

That may be prudent. It may even be necessary. But it should not be confused with transformation. Buffer zones do not end conflicts. They merely ensure that their shockwaves land elsewhere.

Jordan, once again, has been asked to hold weight not of its own making — for the sake of a continent determined to remain insulated.

“Europe has not found a solution in Amman — it has found somewhere stable enough to lean on.”

4. Maximum Pressure 2.0 — Iran at the Brink of Collapse

The opening days of 2026 have pushed Iran’s long-running nuclear confrontation into a more dangerous phase. Washington’s latest sanctions package, sharply focused on enrichment facilities and financial arteries, is not designed to persuade. It is designed to suffocate. At the same time, Israel’s shadow conflict with Tehran is becoming less discreet, less deniable, and far more visible to regional actors watching closely.

Inside Iran, pressure is no longer abstract. Protests now stretch from Tehran’s Grand Bazaar to provincial hospitals in Ilam — a geographical spread that matters. These are not isolated outbursts, nor are they easily contained. The slogans have hardened. Reform has quietly left the conversation. What remains is something far more threatening to the clerical establishment: rejection.

From a British perspective, this moment feels structurally familiar. Regimes rarely fall when pressure is external alone. They wobble when internal stress aligns with international isolation. Iran is now testing that alignment. The collapsing rial, the tightening sanctions, and the visible erosion of state authority are converging into a single question: does the regime absorb the shock, or redirect it outward?

The risk, of course, lies in miscalculation. History suggests that regimes under existential pressure often seek salvation in escalation. A limited strike, a controlled confrontation, a carefully framed provocation — all become tempting when survival feels negotiable. The Persian Gulf, already crowded with rival interests, does not need much encouragement to become combustible.

Our editorial assessment is restrained but sceptical. Maximum pressure does not always produce maximum clarity. It often produces desperate improvisation. And improvisation, in a region layered with unresolved conflicts, rarely ends cleanly.

The world may soon discover whether Iran chooses retreat, repression, or reaction. None of those options come without cost — but one of them risks spreading the bill far beyond Tehran.

“When pressure closes every door, regimes tend to reach for the window — no matter how high the fall.”

5. The Dragon and the Tiger — Seoul Walks the Narrow Path

President Lee Jae-myung’s four-day visit to Beijing in early January was less a diplomatic flourish and more an exercise in survival. In a Pacific region increasingly organised around confrontation, South Korea is attempting something unfashionable: balance.

Lee’s discussions with Chinese leaders focused on “regional de-escalation”, a phrase that carries more weight in Seoul than it does in Washington. South Korea remains an unquestioned military ally of the United States, bound by treaty and geography. But its economy tells a different story. China is not a strategic option; it is a structural reality.

From a British vantage point, this visit reads as a reminder that middle powers still exist — and that they resent being reduced to binary choices. Seoul is not interested in choosing sides. It is interested in avoiding collapse. That may sound unheroic, but it is strategically rational.

Lee’s message was subtle but firm: security alignment does not require economic submission. In an era where superpowers prefer clarity over complexity, such positioning is risky. It invites suspicion from both camps. Yet for South Korea, the alternative is worse — becoming collateral in a contest it did not design.

The real test lies ahead. Tensions along the 38th parallel have a habit of resurfacing at politically inconvenient moments. If regional pressures intensify, Seoul’s room for manoeuvre will narrow. Autonomy, unlike alliances, must be actively defended.

Whether Lee’s “middle path” survives 2026 will depend less on diplomacy and more on discipline — the discipline to disappoint powerful partners without provoking them.

“In a world of giants, survival often depends on knowing how not to choose.”

6. The AI Winter — When the Hype Finally Pays Rent

The technology sector has entered a less glamorous phase. After three years of relentless optimism, early 2026 finds investors asking an unfashionable question: where is the money?

More than $400 billion was poured into AI infrastructure in 2025 alone. Data centres multiplied. Valuations soared. Promises proliferated. What failed to keep pace was revenue. The result is what analysts politely call the “Great Calibration” — a retreat from fantasy towards accounting.

From a British perspective, this moment is overdue. Technological revolutions rarely unfold as advertised. They begin loudly, overpromise shamelessly, and then quietly settle into something usable. AI appears to be following that script with admirable discipline.

Capital is now moving away from speculative startups and towards firms capable of turning computation into cash flow. The bubble has not burst. It has deflated — a far more uncomfortable process, as it forces investors to remain present while expectations adjust downward.

This does not signal failure. It signals maturity. AI will continue to reshape work, consumption and decision-making. But it will do so as infrastructure, not spectacle. The era of effortless disruption is ending. The era of incremental returns has begun.

For Silicon Valley, accustomed to narrative dominance, this is an unfamiliar climate. For markets, it is a necessary correction.

“Innovation becomes useful only when someone is prepared to pay for it.”

7. FTSE 10,000 — Britain’s Unfashionable Moment of Vindication

On 6 January, the FTSE 100 crossed the 10,000 mark — a milestone once dismissed as improbable, if not irrelevant. Yet here it is, quietly undermining a decade of assumptions about Britain’s economic decline.

While American markets wrestle with the cooling of AI-driven exuberance, London’s supposedly dull mix of banking, defence, mining and energy has found new admirers. Stability, dividends and cash flow have returned to fashion. Britain, for once, looks boring in precisely the right way.

From a British editorial standpoint, this moment deserves restraint rather than celebration. Index performance is not national prosperity. A rising FTSE does little for high streets struggling under inflation and wage pressure. The disconnect remains real.

Still, the symbolism matters. Britain’s economy has been written off before — often loudly and prematurely. This rally does not redeem past mistakes, but it challenges the idea that modern economies must chase every technological frenzy to remain relevant.

Sometimes, resilience looks unexciting. And sometimes, that is the point.

“Markets reward patience far more often than they reward fashion.”

8. The Venezuelan Premium — Oil Prices Feel the Shock

The removal of Nicolás Maduro has sent a ripple through global energy markets. Brent crude pushed past $62, driven not by shortage, but by uncertainty. Traders are now pricing in what might best be described as a “reconstruction premium”.

In theory, Venezuela’s return to Western energy markets should increase supply. In practice, the timeline is unclear. Infrastructure is degraded. Legal frameworks are unstable. Control remains contested. Audits, security arrangements and political negotiations will take months, not weeks.

From a British energy perspective, the spike illustrates a familiar truth: oil markets dislike transition more than scarcity. The promise of future abundance does little to calm immediate anxiety.

For major energy firms, the opportunity is obvious. For central banks preparing to ease policy, the timing is inconvenient. Inflation, once thought tamed, is again exposed to geopolitical turbulence.

Venezuela’s oil, long dormant, has reclaimed its traditional role — not as a commodity, but as leverage.

“Oil does not need to flow to influence the world; it merely needs to be uncertain.”

9. The Market Paradox — Records Without Reassurance

The opening days of 2026 delivered a spectacle that would have seemed absurd in any earlier era. As a sitting president was dragged before a U.S. court, Iran edged closer to open confrontation, and geopolitical norms continued to fray, global equity markets responded with celebration. The Nikkei climbed to new highs. The Dow followed suit. Optimism, it seems, has become stubbornly detached from reality.

This is not resilience in the classical sense. It is compartmentalisation.

Markets today operate on the assumption that political chaos can be localised, managed, and ultimately ignored. War is treated as background noise. Regime change as a headline risk to be arbitraged. The belief underpinning this behaviour is simple: efficiency will outpace instability, and central banks will remain the final guarantors of calm.

From a British perspective, this confidence feels increasingly performative. Markets are no longer responding to the world as it exists, but to a carefully curated abstraction of it — one where supply chains always adapt, liquidity always appears, and political decisions never spiral beyond their intended scope.

History offers little comfort here. Periods of extreme optimism rarely coincide with periods of genuine stability. More often, they signal a collective refusal to engage with accumulating risk. The longer the dissonance persists, the more violent the eventual correction tends to be.

What makes this moment distinct is not ignorance, but awareness. Investors are not unaware of the fires burning below. They are choosing, consciously, to price them out. The penthouse view remains spectacular — for now.

The question is not whether markets will eventually react to geopolitical gravity, but how much damage will already be embedded by the time they do.

“Markets do not deny reality forever — they merely delay the invoice.”

10. Britain’s Zombie Economy — When the Numbers Stop Pretending

While the FTSE’s ascent dominates headlines, a quieter and more uncomfortable story is unfolding across Britain’s industrial landscape. According to the Resolution Foundation’s January assessment, 2026 is set to become the year of reckoning for so-called “zombie firms” — businesses that have survived not through productivity or innovation, but through prolonged access to cheap credit and temporary state support.

That era has now ended.

Interest rates near 5%, elevated energy costs, and tightening credit conditions have stripped these companies of oxygen. What economists describe as “creative destruction” is, in practice, a wave of closures, redundancies and regional pain. For policymakers, this purge is framed as necessary. For workers, it feels abrupt and unforgiving.

From a British editorial standpoint, the dilemma is stark. An economy cannot remain competitive while sustaining thousands of firms that exist only on borrowed time. Yet allowing them to collapse without a parallel strategy for labour transition risks deepening inequality and regional resentment — dynamics Britain knows all too well.

The timing is politically awkward. A rising stock market creates the illusion of recovery just as entire sectors face contraction. Productivity may improve on paper, but social cohesion rarely follows balance sheets automatically. History suggests that economic cleansing, when poorly managed, leaves scars far deeper than inefficiency ever did.

Britain is not wrong to confront this problem. It may, however, be dangerously complacent about who pays the price. Rebalancing an economy is not merely a financial exercise; it is a social one. Ignore that distinction, and today’s correction becomes tomorrow’s backlash.

“An economy can shed inefficiency quickly — but it takes far longer to rebuild trust.”